Living with CPT2

I am one of the very few people to have been diagnosed with a genetic disorder called Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II Deficiency, or "CPT2 Deficiency". In between episodes, life with CPT2 is very normal. However, during an episode CPT2 patients experience muscle pain, rhabdomyolysis, myoglobinuria and other unpleasant symptoms. I will use this blog to periodically describe my experiences with CPT2 in the hopes that others with the disorder will find it useful.

Thursday, September 8, 2022

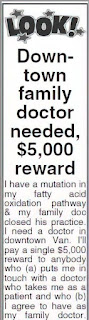

British Columbia could use some Canadian-style healthcare

Monday, June 20, 2022

COVID didn't kill me

Ever since the early reports about a new virus in China started coming in during late 2019, I worried about how the virus would interact with CPT2 deficiency. My worries were magnified greatly when I heard two anecdotal reports from others with CPT2 that they had asymptomatic COVID yet ended up hospitalized because viral infections can trigger an episode.

I tested positive for COVID on a rapid test on January 18, 2022. At that point I'd had a total of four vaccinations (the regular 2 mRNA vaccines and 2 boosters).

I was barely symptomatic. I had a headache and sniffles. However, because of the known risk of any viral infection to somebody with CPT2 deficiency, I stayed off my feet for a week and drank an ungodly amount of Gatorade.

I recovered quickly, and the only thing that has changed is that I may be slightly more tired. Frankly I think the fatigue is due to things other than long COVID, but who knows.

I'm so grateful I was able to get vaccinated and boosted. It turned what could have been a CPT2 disaster into more of an annoyance than anything else.

***

Note that there are many genes involved in CPT2 production. I have two different kinds of mutation, one on each allele. If you have CPT2, it may well involve different mutations, so my experience does not predict your risk of a CPT2 issue with COVID.

***

Added 22-06-22: This raises the question about how to deal with COVID going forward. My risk level is pretty much "same as others in my age range" (now that I know it didn't negatively interact with my version of CPT2). I asked myself "what even are you waiting for in order to relax your restrictions?" I've now had 5 immune events (vaccines + infection), and as far as I know there isn't anything on the way that will be able to outpace the virus' ability to mutate into a version that has pretty good immune escape. I worry a lot about long COVID, less so about acute COVID (because vaccines do mitigate the risk of death down to an acceptable level, and Paxlovid is there to fill in any gaps).

The bottom line is that I can't identify any change that will be a clean demarcation between "be super careful" and "back to normal". The choice is thus between staying super careful forever and figuring out how I want to live for the next decades. If British Columbia took seriously the risks faced by immunocompromised people and those with chronic illness, I'd absolutely be part of that effort -- it is something I've been doing for years now. However, I don't know how much risk mitigation I'm providing others by being the only person in the grocery store wearing a mask.

Ultimately my conclusion is that (a) I've taken all of the steps I can to reduce my risk of serious injury or death; (b) everybody I'm in regular contact with is low risk (either via vaccination or other factors such as age); (c) given the piss-poor public health efforts in place in British Columbia where I live, any steps I take to protect others (primarily wearing a mask whenever I'm not home) probably only make a de minimis change - if any - in the risk level of those at high risk.

The logical answer - I think - is that I can relax my protocols significantly, to a level where I'd be ok with those staying in place all of my life. Basically, mask when indoors for more than a few minutes in proximity to somebody at high risk, isolate for 2 weeks if I test positive, and respect any request to put on a mask.

Wednesday, September 8, 2021

Invisible Illnesses and Covid-19

It is terrifying to have an invisible illness during Covid-19. Mine is a fatty acid oxidation disorder (CPT2). I know of somebody with CPT2 who ended up on dialysis after catching Covid-19. His only Covid-19 symptom was a high fever (vaccinated, so asymptomatic other than the fever), but unfortunately high fevers and viral infections are well known and powerful triggers for CPT2 muscle breakdown (and loose muscle fibers are metabolized in the kidneys, up to the point of kidney failure).

The thing about CPT2 is that we look totally normal. Unless I'm having an episode you can't tell I'm a mutant no matter how hard you look. This means that when I ask somebody to please pull their mask up to cover their nose, I'm asking because catching Covid-19 means I'm almost guaranteed a trip to the hospital. Apart from my own suffering and injury, that trip to the hospital means that some other person who needs a hospital bed will be denied one. I'm not being paranoid. I'm not being selfish. I'm taking a reasonable precaution from a place of very high vulerability.

If I had a visible illness like ALS, I'd be far less likely to be yelled at or even violently attacked for simply asking somebody to follow the rules. But Fatty Acid Oxidation Disorders are not visible.

We need more awareness of invisible illnesses. I've been made to wait as long as 8 hours in the ER because I'm not visibly bleeding -- but when they finally see me and do a blood test for CK, the doctor inevitably says something like "wow, you shouldn't have been kept waiting, this is an emergency" and I get admitted. Unless you're bleeding or claiming heart issues, you are pretty much at the bottom of the triage list. This needs to change. Of course, for my fellow CPT2 patients, a quick tip: I've printed a card explaining what CPT2 is and carry it on me; I give it to the triage nurse and add "I'm really worried because I'm having massive muscle breakdown and my heart is a muscle". That at least gets me a quick blood draw, and during an episode, the blood draw results always bump me up to the top of the triage list.

Saturday, December 14, 2019

Anything that slows digestion is a terrible idea for CPT2 patients

Just stop reading for now if you're eating or easily grossed out. Because what follows sucks. And is not at all compatible with avoiding nausea.

On Tuesday I was feeling mostly ok until mid-day, when I started to burp with a sulphur smell. That was super-weird and had some nausea, but I figured maybe I ate something that was causing it. By Tuesday night I was feeling sick but at that point I'd only eaten an english muffin for breakfast and was worried that my carb intake was too low, putting me at risk of a CPT2 episode. I used cannabis as an antiemetic (thank you, Canada, for making that easy to do) and I was able to eat two pieces of bread.

When I woke up on Wednesday morning, I was feeling very sick and very full. A side effect of Trulicity is that it is capable of slowing digestion. What I didn't know is that it would effectively stop my digestion. I couldn't eat more because there was literally no place for it to go. I tried to stay hydrated and had sports drinks with glucose to stave off muscle breakdown, but by Wednesday evening I was feeling pretty weak. On top of that, I tried using cannabis as an antiemetic Wednesday night but I still couldn't do more than slowly sip liquids. Nothing was happening in my digestive system -- nothing but liquid could go in, and nothing was coming out (nothing had come out since Tuesday morning).

On Thursday I mostly stayed in bed and felt miserable (though I was able to get work done thanks to my laptop), and I was hoping that by staying largely immobile I would avoid triggering muscle breakdown. By midday, though, I was in terrible stomach pain (which I would have just lived with) but I was also feeling muscle breakdown (which is an immediate trip to the hospital). I packed a hospital bag, mostly in a daze, and went to Vancouver General. I have large, 4 x 6 cards printed with my ER protocol on it and they have notes in their system about how to handle me, so I was in the back having a D10 drip in under an hour. This probably kept me from being hospitalized overnight. Another hour or two without IV sugars and I would have been in real trouble. They also administered carnitine and an antiemetic. You'd think the antiemetic was a good idea, because I was able to drink juice and eat a total of four small crackers, but it created the false impression that I was on the mend.

My CK results came back and they were only about double the top end of normal. For people with regular muscle metabolism, that might be a problem, but for a CPT2 patient, anything under around 3,000 is pretty welcome news. I was actually under 500. The rest of my bloodwork showed inflammatory markers and indications of a viral infection.

Going through my CPT2 triggers, I had quite a few. The nausea meant that I wasn't getting enough carbs and that I wasn't able to get enough sleep -- two triggers right there. A viral infection is a trigger (even through I was outwardly asymptomatic for a virus, though I got a slightly sore throat a day later). I am in the middle of a few work emergencies, so I also had stress, yet another trigger. And to top it off, keeping the room cold felt good for my nausea, but temperatures extremes are yet another trigger. Normally it takes me at least three triggers to become symptomatic (the exception is not eating enough combined with exercise, which are the two triggers that are enough in combination). But I was now looking at five triggers, and one of them was the big one -- not enough carbs. Making it even worse, it wasn't a trigger I could fix on my own because the Trulicity had stopped my ability to eat and even limited my liquid intake.

Back at the hospital, though, my second CK came in an it wasn't climbing. Because the hospital has shared rooms and the stress and insomnia caused by sharing a room with a really sick person has, in the past, made me actually get worse in the hospital, the doctors told me it was my choice -- I could go home or get admitted (because I knew my body and how it responds better than they did). After going over the pros and cons, I decided that going home would be the right move. So I went home Thursday night. While the antiemetic was still highly effective, I was able to do work that night (so less catching up to do later).

On Friday I had a work meeting that I just couldn't cancel or move (can't elaborate -- when you work with high tech and are a lawyer, everything has a non-disclosure agreement or privilege, sorry). After that meeting, I was hoping that I'd eliminated enough of the Trulicity that I could try something more substantial than sports drinks. I had a bowl of matzoh ball soup. Boy, did I regret doing that later.

By Friday mid-afternoon, I was experiencing severe stomach pain and an incredible amount of reflux (despite being on Losec, or as Americans know it, Prilosec). I couldn't eat. The sulphur burp thing was making me crazy. My muscles really hurt, but I thought that it was soreness from the earlier breakdown rather than renewed breakdown. I got into bed, cancelled my evening work thing, and this atheist, non-practicing, culturally Jewish man suddenly found found himself asking G-d to please start my digestion again and make me ok.

I kept thinking I was going to throw up, but never quite got there until early evening. I went to the bathroom and had dry heaves for maybe 30 minutes. But the weird thing about it was that when you throw up, you normally feel something in your stomach. All I felt was pain between my solar plexus and my throat. I went back to bed and realized that I'd been taking my medication all week but wasn't digesting anything. I was -- and still am -- terrified that all my meds will get digested simultaneously once my digestion starts back up. I don't think that's the case, because I have BPH and the Flomax was clearly still working, so at least one pill was being at least partially digested every day. But it is something I wish I'd through to ask about while I was at the hospital. Had I thought about it, it would probably have switched my choice from "go home" to "get admitted". Hopefully I never again have the circumstances necessary to put that lesson to use.

I thought I was literally unable to throw up because the Trulicity had stopped my digestive system well enough that even putting it in reverse wasn't possible. If that's true, then the Trulicity was finally wearing off, because by around 9 or 10 pm, I went to the bathroom with more nausea. This time, however, it was literally the most violent vomiting I'd ever experienced. My entire body seized up in pain. Making this a weirdly iterative experience, the vomit itself smelled a little like, well, ok this is gross but feces. "Fecal vomiting occurs when the bowel is obstructed for some reason, and intestinal contents cannot move normally". I need to thank my late father for giving me the courage to share something this embarrassing so that my experience could help others (he experienced it while battling cancer). This is now a red line for me: If I experience it again, it means that there could be a blockage and I have to go in. I'm pretty sure this was a quasi-blockage caused by the Trulicity, but if it recurs I can't take the risk, just in case.

In case you were wondering why I mentioned the Indian food leftovers I'd had on Tuesday, here it is: I threw up a lot. First came the matzoh balls, then the Indian food. It had been sitting there for 72 hours. My theory is that it was being held, undigested, at room temperature for 72 hours, allowing bacteria to grow. Basically, food poisoning that resulted from the unsafe food handling practice of leaving food at body temperature for 3 days -- but a practice that was caused by my own body's failure to clear any of it from my stomach. I could be wrong as to that piece, but it doesn't matter to the outcome. It was the most pain I'd ever felt from throwing up. I was positive I was going to aspirate the vomit, which added an element of terror to the whole experience.

After several more sessions in the bathroom, I got into bed around midnight. But after 30 minutes of trying to sleep, I couldn't. Every time I moved my body, I felt stuff gurgling in my stomach and felt like throwing up. The hospital's antiemetic had apparently been cleared by my body. So I went to the next best (and much easier) thing: More weed. After hazing about 1/4 gram of cannabis, I felt my eyes grow heavy and I was able to move around on the bed without feeling I was about to vomit.

When I awoke this morning (Saturday, since I expect I may add more to this if something else happens from this episode), I felt somewhat better, but still knew that my digestion wasn't working. After all, I hadn't voided my bowels in 96 hours, and to put it lightly, there was nothing in the chamber. Given that last night I threw up food I had on Monday, it isn't surprising that there was nothing to void.

As a side note, this entire time I was monitoring the colour of my urine. This isn't optional for CPT2 patients. If it is dark you see, you need an IV (hey, just made that up!). It got slightly dark from dehydration, but that quickly reversed when I had water. So I haven't (yet) gone back to the hospital.

As I sit here writing this, I'm feeling pretty sick. I still can't eat solid food. I can't even get myself to drink juice. Just sugar water (like sports drinks). And just enough to keep my muscles from breaking down.

The half-life of Trulicity is about 5 days, so I might have a few more days of misery. But I'm hoping that the worst is now behind me. I have an exciting new project I'm working on with a really smart AI programmer here and I've got two new patent applications to file, and those are things I enjoy doing. So I'm hoping that I feel well enough to function by tomorrow morning (I'd say tonight, but the combination of living in a fact-based reality and the fact that I still can't even drink juice tell me it isn't about to happen).

So, what are the lessons? First, we need to proactively ask about any digestive effects of any medication we take. If I was in charge of the FDA or Health Canada, I'd list Trulicity as contraindicated for any FOD/CPT2 patient. But CPT2 is so rare that of course it isn't listed as something that makes Trulicity contraindicated. However, I have a new rule: Ask whether any new medication, or new dose of existing medication, is capable of causing any impact on the speed of digestion or the ability to absorb carbohydrates. Anything that inhibits my ability to get sugar into my blood needs to have benefits that are absolutely necessary to survival. Otherwise, it is just too great a risk.

I can't say that Trulicity is a bad idea for everybody with CPT2. It does have benefits, and maybe the effect it has on me is much stronger than on the average person. Maybe. But I can say that before taking it, a long discussion with a doctor well versed in fatty acid oxidation disorders is strongly advised. Take it from the guy who hasn't digested any solid food or opaque liquid in four days and therefore got so tired writing this that he's heading back to bed.

After all that gross stuff, here is the mandatory unicorn chaser:

[Update 1] It is Sunday morning, and I am finally starting to feel more normal. I started feeling new muscle pain and knew that sports drinks alone weren't going to stave off a CPT2 episode forever. I had a little bit of pasta last night and despite some unsettling stomach pain, it didn't come back up. As of this morning, it feels like it has been digested. I'm going to have more pasta in a few minutes and if that stays down, by tonight I'll be able to eat more. I'm optimistic that I'm past the scary part, but as my head clears I'm all the more surprised that I didn't realize the risks associated with slowing my digestion would be exponentially more dangerous than for somebody with normal fatty acid metabolism.

[Update 2] It is Sunday afternoon (though around 4:45 pm in Vancouver, in December, it sure looks like night outside). I was able to have Annie's brand shells and cheese (exactly 15% of calories from fat, so I'm allowed to eat that!). I ate it for lunch and I feel ok. It isn't digesting at the normal speed (I'm definitely not close to hungry), but it is digesting. I know it is because the muscle pain has finally subsided and there are no signs of muscle fibers in my urine (I know, gross, but dark urine is a give-away that you need to get looked at by a doctor). I'm pretty hopeful that I'll be ok in the morning.

[Update 3] It is Monday late morning and I had a pretty normal amount of food yesterday (bland, but normal). When I woke up I was slightly nauseous but it seems to be clearing up. I'm not hungry at all today, so it has been sports drinks this morning for CPT2 safety. The elimination half-life for Trulicity appears to be 5 days. I'm a little over 6-1/2 days from taking it. So I'm not surprised I'm still slightly symptomatic/nauseous. Yet another lesson: Check half life of a medication before you take it at that dose for the first time.

Tuesday, August 20, 2019

My ER visit triggered CPT2 and landed me in the hospital

I was sick from Friday until Monday. I had a bad sore throat and a fever. I decided to go to the walk-in clinic on Monday and was given antibiotics and a strep swab. While waiting for the antibiotics, I took care of an outstanding labwork order that included a CK measurement. My CK was 109, well below the 165 that is the upper limit of normal. In other words, careful diet management over the weekend avoided my illness turning into a CPT2 episode. If only it had ended there.

I started having a cough and when my pulse oximeter read only 91, I decided to go to the ER.

When I arrived, the first thing I did was hand them my card. They said basically "no thanks, hand it to the triage nurse". A while later, I was called to see the triage nurse. I again said I have CPT2 and handed her my ER protocol card. She held it for perhaps 30 seconds glancing between me and the card. In retrospect, she was either a remarkable speed reader or just pretended to read the card (or maybe she skimmed it). It was a very busy day in the ER and I suspect she was under a lot of pressure to move the line along.

After waiting for a long time (total time sitting in the ER waiting room was around 6 hours, so the blood draw was likely after about 90 minutes) I was given a blood test, but they didn't order CK. At this point I was worried that the stress of being in a standing-room-only waiting room could potentially trigger a CPT2 episode. When they first said they would order a blood test, I asked them to please add CK, and they said they would, but when my blood was drawn, the order didn't include CK. I asked the person taking the blood to please fix this and add a CK reading. I later learned that CK wasn't run initially, and it wasn't until much later, when I was symptomatic, that they read the CK. It turns out that it was around 1,000 at that time.

It is worth remembering that had they followed my ER protocol, I would have already been on a D10 drip, so I'd be home now instead of writing this from a hospital bed. If they had fed me as the protocol required, that also would have avoided this whole episode. But they didn't, and I was sent back to the waiting room to, well, wait. And wait. And wait.

There was a vending machine there, but all of the solid food snacks were too high in fat to be helpful. However, there was also a soda machine that had orange juice, so I kept up my carb intake that way. Sadly, orange juice failed me.

I started to feel leg pain, but what is scarier is that my earlier cough was masking muscle breakdown pain in my chest, upper back, and most frightening, my diaphragm (you know, the muscle that lets you breathe). I figured the pain was from the coughs. It wasn't. Soon I was in pretty severe pain. Luckily, my long ER wait was finally up and I was called back. At that point, all of the breathing issues that brought me to the ER in the first place had resolved on their own. However, I now had a much bigger problem. They re-ran my CK and it was up to 3,000. I was finally started on D10 and given juice. A couple of hours later it was 6,000.

So what went wrong? First off, they didn't follow my ER protocol. That sucked, but I should have been way more pushy about it. While I lived in the US I would have been (I know this because I once asked a US hospital's ER staff to let their risk management department know they were ignoring my ER protocol). But this is Canada, and that kind of behavior just isn't done (though it will be done next time). So my second error was not becoming hyper-insistent and pulling out my "I'm a graduate of Harvard Law and I know you should be following this -- who is your supervisor" persona.

My third error was not adding up triggers. I know triggers. I maintain a well researched and sourced list of triggers. Infection is a trigger, and I definitely had that. Fever is a trigger, and I'd had that all weekend and probably part of Monday. Anxiety is a trigger -- and waiting in that ER lobby for endless hours certainly stressed me out. I've never had a CPT2 episode with less than 3 triggers (with one exception -- the dual triggers of not eating enough food and exercising too hard). However, I've had plenty of episodes with all kinds of mixtures of three or more triggers.

Again, the ER protocol was designed to avoid just this scenario. CPT2 episodes can cause what my wife has aptly named "brain fog". It is likely a result of hypoglycemia that is part and parcel of the CPT2 experience. In fact, this cognitive fog was once misdiagnosed as a severe case of ADHD. By the time I had my blood test, it was too late for me to avoid this on my own, as the cognitive fog had set in. The reason I had cards printed in the first place was because CPT2 episodes often made me too scattered to properly advocate for my own care. As a side note, like most invisible illnesses, CPT2 is only an issue during an episode. There is no cognitive fog unless I'm in the midst of an episode.

The good news is that the VCH Metabolic Disease Clinic consulted with the ER doctors by phone late at night, and visited me the next morning. I feel like they are on top of my recovery. That same clinic was the source of the text of the ER protocol on the card, which makes it really beyond comprehension that the triage staff at the ER didn't follow a protocol written by specialists using phrasing that no lay person would use.

The lesson here is that ER visits are very stressful, so I need to treat them the same way I would treat a long hike -- by reducing the risk of a CPT2 episode. That means carb-loading prior to visiting the ER, bringing lots of carbs with me to eat in case I have to wait, and having somebody with me in case the cognitive fog kicks in.

With invisible illnesses like CPT2, we are absolutely fine until we're not. Then we're absolutely fine again. There is nothing visible from the outside that tells people we're at higher risk than the person sitting next to us. That said, I actually handed the ER protocol card to literally every health care provider I saw on that visit, and nobody followed it, so I'm not sure what more I could have done to make my invisible illness more visible. Of course, once a standard method of evaluating body damage showed damage (i.e. the CK results), the invisible illness was suddenly visible to all. But the shame of it is that the entire episode could have been prevented if any one of the providers had taken the ER protocol seriously.

CPT2 returns to TV

The description of Season 1, Episode 1 is "Detective Work: The once-athletic Angel, 23, suffers from episodes of muscle pain so severe she often can't move. As she begins a nursing career, she needs answers."

Given the title of the blog I'm posting on, it shouldn't surprise anyone that her disease is diagnosed as CPT2 deficiency.

First, the fact that she spent nearly a decade trying to figure out her diagnosis means that I personally consider this blog to have failed her. The idea of posting my experiences was to help people like her (seeking diagnosis) by giving them something to discuss with their doctor. It also means that the super-helpful Facebook FOD group and the great, more specific "What you can do despite CPT2" Facebook group have failed her. They are great resources, but somehow didn't place high enough in search results for searches done for the key symptoms of CPT2 episodes. I personally think the quickest answers come from the Google Group for CPT2, but that too didn't help. As much as the CPT2 community is a strong one, we need to do much better at getting listed in response to searches for symptoms of CPT2 attacks.

So, here is a quick search-engine-friendly, somewhat incomplete list of symptoms (note that I do not have advertising on this blog and I'm not trying to monetize any improved search engine results, I just want people with CPT2 to be able to find the resources they need).

Coca-Cola or Coke colored urine, dark pee, dark red or other evidence of blood in the urine (since many quick tests just test for iron in the urine and call it "blood", somebody with muscle fibers in their urine will test positive for blood in the urine if the test just looks for iron).

Muscle weakness, exercise makes my legs hurt so much I can't bend them, I suddenly get very stiff and painful muscles.

When I'm stressed out, I get muscle pain. When I don't sleep enough, my muscles hurt. When I eat meals with too much fat, my muscles ache. When I don't eat enough, I can't walk very far before I get muscle failure.

I got propofol infusion syndrome PIS or hyperthermia from an anesthetic that act on fatty acid.

When I tried Atkins, Paleo, low carb, no carb diet, my muscles hurt a lot.

My doctor doesn't know what's wrong with me, but my CK is sometimes really high.

My CK was over 10,000.

My CK was over 20,000

My CK was over 30,000

My CK was over 40,000

My CK was over 50,000

My CK was over 60,000

My CK was over 70,000

My CK was over 80,000

My CK was over 90,000

My CK was over 100,000

I got rhabdomyolysis.

If these help one person find this blog and then go on to the community groups I linked at the top, I'll call it a success.

Thursday, July 26, 2018

What I learned spending a year eating under 15% calories from fat

My diet was:

1. Prescription grade MCT Powder every morning, approximately 140 calories (provided free of charge by the BC government -- Canadian health care is one of the things that makes Canada awesome!).

2. Eating at home: Under 15% of calories from fat. Sounds simple, but it isn't. Let's put it this way: 100 grams of corn has 96 calories and 1.5 grams of fat. At 9 calories per gram, that is 13.5% of calories from fat. The baseline fat in many foods we consider fat-free is actually more than zero.

2(a): Watch out! In the US, if it is less than 0.5 grams of fat, they may simply say "zero". You don't normally see food labels list 0.3 grams of fat.

2(b): Canadian products, including "fat free" dairy products, actually DO list fractional grams of fat. Surprise! Many "fat free" dairy products do have fat in them. Read the label.

2(c): I normally want every single ingredient to have less than 15% of calories from fat. That way I actually eat less than 15% calories from fat -- because I assume that through the course of the day I may make errors and this lets me make a mistake (such as when they give me "skim milk" creamer at a restaurant that is really 2%) without blowing the 15% mark.

3. Eating away from home: This requires a bag of tricks.

3(a) First, nothing on the menu is going to work. Seriously. I can count on one finger (or less) the number of times I was able to just order a menu item without having to have a conversation with the server about fat content.

3(b) Second, pizza. Pizza is a fantastic choice, with a giant caveat: "I'd like to order the Margherita Pizza, but with no cheese. If there is any oil in the pizza sauce, please just put some tomato slices on it instead." Done this way, it is basically bread and vegetables. Some breads have more than 15% of calories from fat, but it isn't going to destroy your diet ratio. Just offset it...

3(c) Third, offset it. Order some rice or a dry baked potato to eat with the meal. This gives you extra carbs and reduces the overall percentage of calories from fat.

3(d) Fourth, your dessert is always fruit. Always. You don't have a choice (except periodically sorbet when it is available).

3(e) Fifth, you don't get to order fancy coffee either unless it is fat free. One regular latte pretty much blows your ratio for the day.

3(f) Sixth, get creative. Tell the server that you have a muscle disorder and you're medically limited to 15% of calories from fat and you'd like to order a piece of grilled chicken on a roll with no mayo, no cheese, nothing else with fat. Then smile and say "I'm not allowed to eat anything fun anymore, so instead of fries can I have a salad with no cheese, no dressing". The self-deprication prevents the server from getting annoyed with you.

4. Learn math tricks.

4(a) 15% is a difficult thing to calculate on the fly, particularly when you're at the supermarket and looking over dozens of nutritional labels in an hour. What is 15% of 145 calories? Yeh, I don't know either. The good news? It doesn't matter -- use the trick in the next paragraph.

4(b) Long chain fats have 9 calories per gram (medium chain fats have 8 calories per gram, but those with CPT2 can metabolize them, so they don't count against the 15%). It turns out that 9/60=15. In other words 1 gram of fat = 9 calories = 9/60. This makes life simple: You can eat anything that has 1 gram of fat per 60 calories or less. If it has more than 1 gram of fat per 60 calories, you don't get to eat it. Quick test: 4 grams of fat in 218 calories -- OK or not OK? Easy answer: 4x60=240. 240<218, so all good, eat away. What about 6 grams of fat in 250 calories? 6 x 60 = 360. 360 calories > 250 calories, so the amount of fat is too high (i.e. 6 grams of fat requires at least 360 calories to be 15% or less).

5. Protein: I was told by a former nutritionist to stay away from protein. That is not the advice my CPT2 specialist gave me. During an active muscle breakdown episode, protein can be risky since metabolizing muscle fibers and protein both happen in the kidneys, putting them at heightened risk of failure. If I'm not having an episode, I no longer limit my protein (except almost all proteins have fat in them, so I do the "no more than 1 gram of fat per 60 calories" trick.

CHANGES:

I had my second visit with an Adult Metabolic Disease Clinic nutritionist last week, and learned I was doing things almost right. The "almost" was a trick that I'm not allowed to do anymore. I was adjusting the total number of meal calories by ordering juice or pop (with sugar) with my meal so that it would offset the fat calories. It turns out it is far more complex. Yes, you can offset, but only with complex carbohydrates. So a side order of whole wheat bread is all good, but a Pepsi, as delicious as it is, is not a legitimate way for CPT2 patients to offset calories. You can still have sugar pop drinks, but just don't use them to offset calories.

Importantly, I was told to make the carbs I eat as complex as possible. This is itself complex, because whole foods often have more fat than their simple carb counterparts. For example, brown rice has 1.8 grams of fat per 8 ounces. It is still ok, because it has 216 calories (rounding up, 2 x 60 = 180, so brown rice is just fine). But in terms of a fat-free food offsetting other foods with fats, complex carbs aren't a magic bullet.

Also, now that I've moved to Vancouver, I will say that Kombucha is awesome. My nutritionist was clear that Kombucha is sufficiently complex that it is just fine to drink.