My Years in the USA Advocating for Canadian-Style Healthcare

I was born in Montreal, but my parents moved to California when I was 9. My dad was a doctor, and frequently argued with the other doctors in his practice group about how in Canada, he was free to practice medicine while in the US, his hands were tied by the byzantine private insurance system. Sure, he'd say, he's earning more money, but he'd much rather live with the Canadian system because it would let him worry about the health of his patients as his first and only priority. There would be no arguments about whether a procedure was too expensive for an insurance company's shareholders.

In my early 20s, I was diagnosed with a fatty acid oxidation disorder.

For years, I kept my invisible illness (called CPT2 Deficiency) a secret from my doctors. It wasn't that I was embarrassed by it. Instead, it was a deep worry that if my medical records were festooned with references to CPT2, fatty acid oxidation disorders and rhabdomyolysis, I would become uninsurable under the United States' "if you're uninsured, prepare for bankruptcy, death, or both if you get sick" medical system. To protect my kids' ability to get insurance, I never had them tested for CPT2 until after I moved to Canada. Instead, I would check their urine color (and when they were older, asked them to check their own) for signs of rhabdomyolysis. My father's observation that the US medical system was not compatible with obtaining the best health outcomes seemed proven right by my experiences with CPT2.

In 2008, my former classmate (a year ahead of me in graduate school, so while I knew a lot about him, I didn't personally know him) Barack Obama started climbing in the polls and then accumulating lots of convention delegates. His competitor in the primary was Hillary Clinton. While both promised to implement substantial medical reform, I wasn't ready to disclose my illness for fear that McCain would win or that medical reform wouldn't pass Congress. I joined the Obama campaign and worked on his Legal/Voter Protection Team in the primaries. I spent a week in both Pennsylvania and Texas as part of that team.

As the primaries drew to a close, I was given the opportunity to work as a Regional Field Organizer for the general election campaign. I started out managing Fresno County, but eventually ended up in charge of the campaign's efforts in many neighboring areas. There were plenty of reasons to want Senator Obama to become President Obama. There were reasons that were high priority for me even though they didn't directly impact me, such as diversifying the federal judiciary and enforcing federal civil rights laws.

The most powerful incentive for me to work on the campaign, however, was his promise to treat medical care as a basic human right. He would get rid of the ability of insurance companies to refuse coverage because you were born with a problem (that's me); he would require mental health care to be covered in the same way as physical health care; he would, I believed, work hard to decouple poverty and bad health outcomes. I took months off of work to campaign for him.

Part of the training for Regional Field Organizers was to attend "Camp Obama", a multi-day gathering where we learned how to reach voters. A key lesson was to make policy personal. Rather than talking about a universal healthcare system in the abstract, we were told to put it in context by sharing how it impacts us personally. I was inspired and dedicated enough to decide that it was time to "come out" as having an invisible illness. As it turned out, every time I shared my fears about testing my kids for CPT2 deficiency, I moved the needle a lot. Personal stories matter in formulating policy and shaping elections.

At this point, I was "all in". If medical reform didn't pass, I would have a record of a "preexisting condition" -- a condition that, while not necessarily medically fatal, could be fatal to my ability to get medical insurance if I lost my existing coverage.

The Affordable Care Act became law and has survived more than a decade of efforts to dismantle and undermine it.

When the 2016 primary elections delivered Clinton and Trump as nominees, I started telling people I would move to Canada if Trump won. I felt he would be the beginning of the end of the US as I knew it, and I worried deeply that Trump would sabotage the Affordable Care Act, or worse yet, sign legislation to overturn it wholesale.

I moved to Canada weeks after Trump was sworn in.

Canada, Before COVID

When I first moved to Vancouver, I heard rumblings about issues with finding a family doctor, but I had no trouble finding one just a few hundred meters from my front door. I had nothing but good experiences with the system. I was aware that some people were complaining about long waits for procedures, but it seemed to me that the long waits primarily impacted people who didn't have a critically time-sensitive problem (not that long waits are ok in any case, but triaging procedures explained a lot of it to me).

As some people have painfully learned, British Columbia's Medical Services Plan (MSP) doesn't start until start of the fourth calendar month after one moves to BC. I moved in February 2017, which meant that I was covered only by travel insurance until May 1, at which point government care kicked in. Of course, because things just sometimes work that way, I was hospitalized at the end of April -- and my travel insurance refused to cover it, because I had previously been hospitalized for a CPT2 episode. In other words, my long-feared lack of insurability due to the pre-existing condition of CPT2 was finally realized during the last two weeks I ever had to fear it.

My experience in the hospital was as good as I could have expected, and much better than it was during my prior two CPT2 hospitalizations in the United States. Other than a stubborn refusal to give IV opiates as part of the effort to avoid creating new addicts in a city with a horrible overdose problem, which I understood but disagreed with as a blanket one-size-fits-all policy, I had no complaints.

I was seen numerous times a day by physicians. I loved the opportunity to talk to a variety of interns and residents about what it is like to have a fatty acid oxidation disorder (the more doctors who know about it, the better others with FAODs will fare). The nursing staff was unbelievably great. Even the food was acceptable (though it would never be mistaken for gourmet food). When they learned I was paying out of pocket for the care, my primary doctor came in and told me that if I was staying as part of government-provided health care he would keep me for a few more days, but he gave me the option of caring for myself at home to save money. As this was literally my life and health we were talking about, I ended up deciding to just eat the cost of the extra days in the hospital.

Right before COVID hit, I was hospitalized in Canada a second time (my fourth overall), this time at Vancouver General Hospital. By then, I had been accepted as a patient of the Vancouver General Hospital Adult Metabolic Diseases Clinic. In addition to a parade of physicians and nurses seeing me daily, the clinic sent a doctor every day to make sure I was doing well and that the doctors treating me as an inpatient had all of the information they needed to help me heal.

It was at the end of that second hospitalization that I realized that I had been absolutely right to fight for Canadian style healthcare in the United States. I was treated with care, dignity, and a complete disregard for whether I had money. I stayed as an inpatient for a full week, and the only time finances ever came up was when they took my medical services plan number when I first got to the hospital. There were no bills, no copays, no fights to keep me hospitalized when an insurance company decided it was just too expensive. All that mattered was my health. I'd been vindicated in trying to change US healthcare to be more Canadian -- I thought.

Canada, 2020 to Now

I personally witnessed a lot of abuse of medical personnel during the first two years of COVID. A tiny woman (maybe 5 feet tall and 90 pounds if I had to guess) working the front door at VGH's ER asked a huge man (at least 6 feet tall and well over 200 pounds) to please follow the mandatory masking policy. Without hesitation or humanity, he got in her face and screamed -- in the process demonstrating his lung capacity and breathing were undiminished -- that he couldn't wear a mask because his lungs aren't strong enough. Then he called her the N-word (although she looked for all the world like her ancestors were from India, I guess when a racist is searching for a way to insult somebody, all skin tones darker than chalk look alike). He was escorted out by security.

This was a story I saw repeated nearly every time I sought medical care. People intentionally pulling their masks under their noses while in a waiting room (with people, like me, who were extremely clinically vulnerable) and yelling at staff when there were politely asked to cover their noses.

By this point, my family doctor was Dr. Sangeetha Nadarajah. I've had some pretty great doctors in my lifetime, but Dr. Nadarajah was in an entirely different category. She deeply cared that I stay healthy. She understood how CPT2 works by the second time I saw her (so she did the research on her own time -- something no other non-neuromuscular specialist had ever done). She didn't just guide me on my journey as a CPT2 patient, but made me feel she was walking that journey with me. She was caring, but in a way that grew from deep empathy -- a bedside approach that one can be born with, but that can't be taught. She is somebody I consider a

mensch (I'm Jewish and being a mensch is a good thing).

In 2021, I started hearing stories about doctors (many in family practice) quitting because of the stress of dealing with COVID. Not treating the disease. Not helping those with long COVID. Not advising on avoiding COVID. Instead, they were quitting because of the hostility and anger they constantly had to deal with from people wanting vaccine and mask exemptions for no reason other than misinformation about vaccine risks and mask efficacy; because of the dangers of simply being identified as a physician by COVID deniers; because of the inability to keep themselves safe around the worst 5% of Canadians who treated COVID as a fabricated inconvenience instead of the pathogen it is.

In 2022, Dr. Nadarajah told me she was quitting. I immediately felt a combination of sadness and terror. The best doctor I'd ever had no longer felt she could practice family medicine in British Columbia. In a province where one in four people are searching, fruitlessly, for a family doctor, I felt the terror of joining their ranks. Worse, I had an incurable genetic disease that could only be properly managed with a family doctor on board.

Shortly thereafter, Dr. Nadarajah said that she had discussed my case with the doctor in charge of the clinic I had attended, and that he had agreed to take on some of her very high risk patients, me included. After effusively thanking her, I finally let myself exhale. It was going to be ok. I would still have a family doctor necessary to manage my health.

If only the story had ended there, but it didn't. Shortly after being told that the new doctor would be my family doctor, he sent a letter saying that he was closing his practice. The letter included this passage:

I was truly confused because the

British Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons has a practice standard that says that when a physician "decides to end the patient-registrant [doctor] relationship after thoughtful consideration, they must ... where possible, assist the patient in finding another registrant [doctor] or clinic where care can be transferred" and "ensure medical services are provided in the interim period..." I'm not licensed to practice law in British Columbia, so it is entirely possible that I've read the standards as requiring things they do not require, but I was nonetheless shocked that a patient with a serious metabolic condition was terminated by email, and that the efforts to find me a new family doctor were limited to providing a list of websites and mentioning that maybe a friend would help me.

This is when I decided I needed to take out an ad. The math was simple: Without a family doctor, my risk of an early death was unacceptably high. I have three daughters -- 21, 15 and 13 -- and my death or a serious disability would be a disaster for them. With the horrible shortage of family doctors, I was aware that I needed a doctor capable of understanding my condition and properly triaging patient needs. With the existing clinics throughout Vancouver's Lower Mainland bursting at the seams with patients, I knew I'd need a clinic near where I live so that I could jump on any cancellations and avoid travel while suffering an episode. After all, if a 90 minute drive to Delta (near the US border) was followed by a 5 hour wait and a 90 minute drive back, that's all day. Worse, I had already been hospitalized overnight when the anxiety of waiting for eight hours in the VGH waiting room triggered a muscle episode (I was waiting to be seen for lung function issues, and those resolved on their own while I was waiting -- but not before rhabdomyolysis from the stress had set in).

If I couldn't find a doctor within walking (or 5 minute Uber) distance, I would need a doctor who would not have a long wait once I arrived. I have a Nexus card, so I can normally cross the Canada/US border in ten minutes or less. I decided that finding a family doctor just south of the border would be the best course of action if I could not find one locally. At least I'd know I could get treated without waiting for hours among the sick and coughing in a waiting room. The cost of US health insurance would run around $20,000 per year. The cost of cash-pay for services would run $5,000 or so per year (based on a bunch of assumptions -- obviously there is a lot of guesswork involved in calculating how often you'll see a doctor).

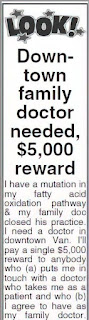

I decided that the financially and medically responsible thing was to run an ad and offer $5,000 on a one time basis to anybody who could hook me up with a local family doctor who could meet my requirements. Of course, it is illegal for a physician in BC to take money to see a patient who is covered by the Medical Services Plan, so I knew that no doctor could take the money. However, I figured that it might be enough to get patients of good and available family doctors to reach out to me with leads. This is the ad that ran in the local papers (I cut it off right before the email address and phone number):

Right after placing the ad (and before she saw it) Dr. Nadarajah reached out to me to ask if I was doing ok. I told her about my situation, and she was not at all happy to see one of her high risk former patients without a family doctor. She said she would make some calls and see if she could find me a family doctor I could walk to (or, during an episode, quickly Uber to). Bear in mind that she had already met her obligation to transfer my care to another family doctor, so this was going above and beyond her professional obligations. She was also careful to encourage me to keep looking on my own in case she couldn't find a place to place me.

I thought I'd get a few calls, but my years of living in the United States left me unprepared for the kindness that beats in the hearts of Canadians. I was (and still am) overwhelmed by the number of leads. Moreover, the only people who mentioned the reward mentioned it as part of a phrase communicating "I'm not interested in the money, but here's a lead..." or "I'm not interested in the money, but here's a charity you could consider". Within a day, I had around 100 leads.

I'm not going to link to my appearances in the media, but my story was picked up by the CBC and CTV, and reached a substantial audience through social media as well. Bear in mind that stress is one of the triggers for a muscle episode, and I found myself starting to stress because I wanted to personally thank everybody who helped -- whether they had a good referral or not. However, as the number of responses kept growing, I knew I didn't have the bandwidth to do that.

I lined up several of the best leads and was starting to reach out when Dr. Nadarajah reached out to tell me that she was able to find a doctor she trusts to take me as a family patient. This was the figurative life preserver I needed, and she was able to throw it to me. The only caveat was that the doctor she referred me to had a huge waiting list, and he would need to meet with me before deciding that my condition was serious enough to merit taking me on immediately.

I contacted the doctor that Dr. Nadarajah referred me to. Within a week, he met with me, went over my condition in detail, and agreed to take me on as a patient. I felt enormous gratitude and relief - even as I worry about the more than a million BC residents unable to fix their lack of family/primary medical care.

Guilt, Privilege, and Fixing Things

This is probably the right spot to air my guilt. I know in my heart that this entire situation was caused by the government of British Columbia letting the healthcare system fail. Whether the collapse started under the BC Liberals (ironically named, as it is the party representing conservative positions) or the current BC NDP party (the party representing liberal positions) has been the subject of a lot of debate, but ultimately it doesn't matter. The buck stops with the current party in power, and with a majority government they could set about fixing things. Instead of fixing things, though, they got busy complaining that the federal government wasn't contributing enough money to the provinces (in Canada, the provinces are in charge of medical care and the federal government provides subsidies). When talking with the media, I noted that finger pointing isn't solving the problem, and that I wished that BC would raise taxes on me and those in a like position and use the revenue to fix the medical system, perhaps seeking reimbursement from the federal government later. After all, a period when patients are dying for lack of care is exactly the wrong time to let affixing blame get in the way of fixing the problem. It turns out that they wouldn't even need to raise taxes, as days after the interviews BC announced it had a very healthy annual budget surplus, well in excess of one billion dollars.

As the previous paragraph indicates, I'm well aware that I'm not the cause of this problem. However, emotionally I can't get over the fact that there are others (around a quarter of people in BC) who are looking for a family doctor but unable to find one. And I literally jumped the queue because of my medical condition. Were it not for my responsibility to my children, I would find that difficult to live with. However, I think most parents would do the same to make sure they were around for their kids.

The true guilt, of course, would have surfaced had my privileged position (having enough money to offer the large reward) made the difference. While knocking on doors and calling voters for the Obama campaign, I never thought that a progressive government (like the BC NDP is supposed to be) would allow single payer healthcare to languish. It never occurred to me that prohibiting free market provision of medical services in favor of a government pays system meant that an incompetent or indifferent government could endanger the health of everybody. It definitely never occurred to me that I would need to offer a reward to find a family doctor.

The bottom line is that the Canadian system was never supposed to work like this. There was supposed to be enough money to pay doctors. There was supposed to be a large enough number of doctors to treat the patients. The egos of those in provincial leadership weren't supposed to lead them to use growing anger over healthcare failures as a lever to get money from the federal government -- rather than simply fixing the problems.

If I was in charge, I would take the following steps:

1. Identify jurisdictions with physician licensing standards similar to British Columbia, and allow licensed physicians from those jurisdictions to provide telemedicine services to residents of BC.

2. Welcome foreign-trained physicians to qualify to practice in BC, providing each with an advocate who will help them navigate everything from immigration to housing to training and licensing.

3. Raise the pay for family practice physicians to be competitive with the pay received by specialists so that the financial incentive to avoid family practice is eliminated.

4. Prohibit family physicians from charging people without government healthcare more than they collect from the government for seeing people with government healthcare. This alone would likely alleviate much of the crisis. Family doctors make far more money on a per capita basis seeing foreign patients than they do seeing BC residents, creating an incentive where non-residents can easily be seen by the same family doctors who claim their practice is too full to take on new BC residents as patients or walk-ins. This is a much bigger issue than most understand, and there are even companies that arrange for international travel to BC for private-pay medical care.

5. Include mental health professionals, such as therapists and psychologists, within the government paid programs. From the overdose crisis to medical service providers such as nurses quitting from the stress of working with COVID patients, it is clear that the cost of providing mental health care is far less than the cost of not providing it.

Was I Wrong in 2008?

The failure of the BC healthcare system and the extraordinary measures it forced me to take have made me reflect hard on whether I was wrong in advocating for a Canadian-style healthcare system in the US during the 2008 election. Ultimately, I do not think I was wrong as a matter of public policy. It is unacceptable to treat medical care as anything other than a basic human right, and a system that conditions medical care on wealth was an utter abomination. The Canadian system, warts and all, is better than a cruel system where poverty plus illness equals death and where insurance companies have a bigger say in healthcare than physicians do.

However, calling a medical system "better than the US healthcare system was in 2008" is faint praise indeed. Furthermore, it is far from clear that the current system in BC is better than the system in place in the states that accepted Medicare funding under the US Affordable Care Act. Yes, the paperwork is crazy-making. The co-pays and deductibles are inhumane. But at least the poor get free healthcare, the middle class gets a large subsidy, and the wealthy, as usual, can take good care of themselves -- and there are enough doctors to provide the care required.

Medicare should be the pride of British Columbia, not a festering and deadly embarrassment.

Everyday Canadians need to insist that their elected representatives show the same level of love and care for their neighbors that everyday Canadians show. That means, if nothing else, making sure that the health of BC residents is a top financial and legislative priority. If elected officials can't treat their neighbors and constituents as they would wish to be treated, they have no business calling themselves Canadians -- and they certainly have no business holding elected office in British Columbia.

The family doctor crisis is an easily fixed problem being cast as an intractable one by politicians who can't be bothered to (or who are afraid to) take the steps necessary to fix it.